John Singleton is publishing my essays, and has asked me to add a few more pieces to. This is the first of the new pieces.

MGG

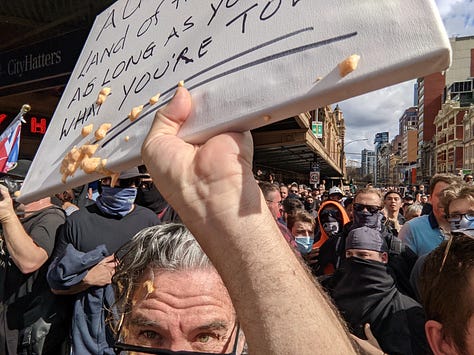

We met at a quiet train station. The ten-kilometre zone was still in place, and today I was choosing to challenge it. In my hands was a sign I had created myself. It read, “Australia, Land of the Free, As long as you do as you’re told.”

Matt Lawson

The police had made it clear that protests against the lockdowns were not allowed, so the sign was an issue. Any police officer who saw it would know exactly where I was going, but where to hide it? I had no bag to conceal it in, and it wouldn’t fit under my jacket.

A few times I left it on a bench seat on the empty station, strategically deciding it was too great a risk to carry, but I kept returning to retrieve it. I had never been a lawbreaker, and I had never lived through times like these, where the police were being brutal to anyone who defied the decrees of the premier.

Then my new friends started turning up. One was a South African woman, well-to-do, demure, and yet determined. Before long I was in her brand-new Land Rover, and with this small gang of (what), we were heading to the city.

We parked in the multi-story car park next to St Vincent’s Hospital, and with my sign in nervous hands, I surveyed the city before me. There was a distinct energy to the view, a hostility that in all my time in Melbourne the city had never had.

As I lingered outside the hospital, wondering how we were going to reach the heart of the city, a big man strode past. He had the air of a leader and was surrounded by small men like me who were feeding off his courage. I joined them and began feeding off him too.

This wasn’t his first protest. He spoke of how violent the police had been, of the arrests and fines, and yet here he was, the battering ram of this little band of brothers, who were now sneaking into the city via the small streets, our ears and eyes peeled for the police.

I had already lost the people I’d driven in with. Fear is a voice that is constantly trying to rationalize why retreating from danger makes logical sense. And there was no logic in proceeding. This small group of men, each stoking their courage, step by doubtful step, had no chance of changing anything. It wasn’t just the city we were up against, but the state, the country, the entire Western World, that had already declared, but in modern speak, that they, the vaccinated, were the chosen ones, and we were the dirty Jews.

The message was so powerful that, apart from a few defiant ones, Melbourne’s entire Jewish community had, without question, complied. Whatever happened today, there would be little to no sympathy for us. And yet still we moved forward, our only solace each other. These strangers.

And then it happened. We reached Bourke Street, and before us was a river of people, all of them like us, unmasked. And as I entered the stream, people who I’d never met, men, shook my hand, patted me on the shoulders, and said, “Welcome, brother.”

I couldn’t recall how long it had been since I first heard the word Covid, but this was the first moment I’d cried. I wasn’t alone. I wasn’t crazy. Here was a river of defiant humans, their faces bare to the elements, and all of them marching in the same direction.

Me and Tom Vogal

It was also now that I met Tom Vogal. I’d known of him for his short film festivals, West Side Shorts, but I had never met the man. Now we still work together, with him as the producer and host of the WTF show.

We took a few selfies together. We took pictures of the crowd and realized that our souls were singing with hope. But then we turned the corner.

The police had already been attacking the protesters. One young boy, eleven years old, had approached them with a sign that read, “Let the children play,” and he had approached them alone. Then, to the horror of the crowd, some of the police officers pepper-sprayed him, smothering his face in their burning foam.

In hindsight, that was the first moment where you realized there were no rules of engagement. They had been taught to hate us and hate us they would.

In the shadow of Parliament House, there would be many scuffles with the police, but our numbers were so great that their chemical batons and gas canisters couldn’t disperse us. Suddenly we were marching down (which), and despite the initial battle with the police, our spirits were high. I don’t even know why; I guess we knew we were right. Even though few, if any, of us knew what we were up against.

Or maybe it was because we had just been tested. The police had tried everything, even brutalizing our children, in order to get us to attack back, to be violent. But we hadn’t.

I remember these young women; they were standing in no man’s land between the police and the protesters, and they were condescendingly provoking the crowd. “Where are the men?” they were asking, as the police left them alone to ask. But us men were here, now surrounded by a greater number of women, and our heads were high and our stride was confident, and I was holding my sign above my head.

And then the crowd thickened. Where Flinders Street met Swanston Street, the police had formed a line. But they were unlike any police we had seen before. They were wearing what looked like plastic storm trooper uniforms. They had helmets with clear plastic shielding their faces, and they had circular transparent shields, and their sergeants were calling us cowards, egging us on to attack.

Even those young women, who had been in the centre before, were back and doing the same. In hindsight, we should have all sat down, a strategy we did in the protests to come. But we were Australians, and we all knew this: all we knew was that we couldn’t be violent. And we knew that because it was clear that they wanted us to be.

It was now that they upped the stakes by producing weapons we’d never seen before. They were rifles that shot gel pellets, but we didn’t know that. From our perspective, they looked like real rifles, and they were aimed at us, but the police officers who were clearly itching to fire, to shoot us.

“Are you going to shoot us?” I heard young men ask, with disgust. “We’re your brothers,” the young men around me were saying.

But the crowd’s disgust didn’t affect the police. Still they aimed their new weapons at us. Still their sergeants called us pussies and urged us to attack.

The standoff would last for what seemed like hours but was only ten minutes or so. A standoff that was cooking to a battle until one man, who I didn’t know then, became a pressure release valve. Arms up in the air, he approached the police, calling for calm. We all watched him. This, the bravest of men.

This was Matt Lawson, and he was walking into history, for a few moments later, at point-blank range, one of the officers shot him, not with one of the new pellet guns, but with a rubber bullet. In that moment, Matthew became the first protester to be shot by the state since the Eureka Stockade.

In shock, and we were all in shock, Matthew, still with his arms up and protected from the pain by adrenaline, turned around and told them to shoot him again. They did.

It was now that the officers unleashed a deluge of pepper spray. Fortunately, my sign prevented their foam from entering my eyes. But as I stumbled back down Flinders Street, surrounded by people covered in pepper spray, including Rukshan, another giant who as yet I didn’t know, the spray worked its way up to my eyes. Until my last clear view, before it rendered me blind, was the police line following us down Flinders Street.

By this time I’d reached Elizabeth Street, but my burning eyes were blind. Later, Rohana would pick me up in our car, and I would talk about this in my first-ever protest rant. A rant where the comments were full of artists, for I was in the arts, and other people wishing the police had used real bullets.

But back on Elizabeth Street, I had begun laughing, for I couldn’t believe that this was Melbourne, my adopted and beloved city that I could no longer see. And I was utterly alone. That was until a woman asked me if I was okay.

“No, I’m blind,” I said.

She then guided me to the footpath and sat me down in the gutter, where several young people, boys and girls, began caring for me. One of them poured milk onto my face, and then another young man took off his top and gave it to me, stating that I could no longer wear mine as it was thick with foam.

I don’t know where the police were, but I knew where I was. I was surrounded by the Australian Spirit. And each of them, with their courage and empathy, was letting me know that we were all worth fighting for, even if the majority of us, including the police, were corrupted by a fear that was being fanned by the state.

That evening, when I had a shower, the water would reignite the pepper spray entangled in my hair, and my entire body would be on fire, including my balls, but like everyone else who was at that protest, instead of being scared off, we fired up. For despite taking our jobs and despite the media convincing our families and friends to ostracize us, we could see that our liberty was under attack, and in that time, the only ones who were prepared to defend it, day in and day out, were us; The Australian Freedom Movement.

~Michael Gray Griffith

Unfortunately I was a witness to that attack on you. I was in lockdown, watching on my phone, as the police shot you and then handcuffed you. Unbelievable behaviour from the so called police who should have protected you. God bless. You have suffered since then but so glad you are documenting this tragic event. This country is absolutely corrupt.

The moment that made my eyes wide open, never to close again, never to trust again. It is not my world, they can have it. The scary thing is 99% of victorians don’t even know it happened.