This was the first aisle, and her three young kids were heading off simultaneously in three different directions, returning to her trolley with brightly packaged processed food—all of which she replaced on the shelf.

At one point, she stopped to read the ingredients. Next to her, her son did his best to sell her the item, but he wasn’t convincing, and she put it back.

The reason I was observing them all was the mother’s face, at the core of this family. She looked deeply concerned—frightened, even—about the price of everything, despite this being Aldi.

I wonder if, before these children were even born, she ever imagined there might come a time in Australia, as politicians sang the praises of a "robust economy," when she wouldn’t be able to afford to feed them.

The mortgage, the rent, the bills, the car... and food.

So many people tell me they are considering living in a bus or a van, traveling from town to town, like asylum seekers from a failing dream.

But even out here, the same poverty waits—only now you must add fuel.

Some caravan parks charge over $80 a night. While some towns offer their showgrounds as free or modestly priced camping sites with limited-duration stays, others are actively trying to close their free campgrounds.

We shouldn’t be like this, and we know it.

With all this mineral wealth, our national debt shouldn’t exist, and our politicians shouldn’t have to obfuscate as they attempt to sell us their economic credentials—on their way to board a private jet.

And while they always strive to make it clear that it’s not clear what happened to the "lucky" in our "lucky country," not even the raw truth would soothe this mother’s concerns.

Another mother told me her food bill alone for three kids and her partner now ranges from seventy to over a hundred dollars a day. She explained how she avoids the central aisles—home to brightly packaged, cheap, and nutritionally questionable fast food—and hunts for deals in the meat, dairy, and vegetable sections. But even that is getting harder.

“Is it sustainable?” I asked her.

She shrugged.

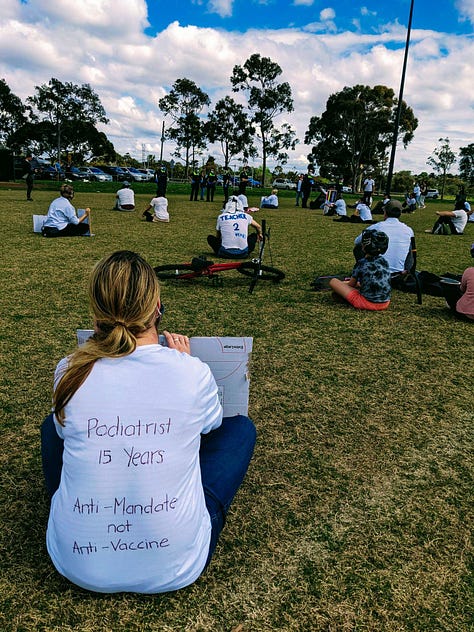

There is another mother’s face enshrined in my mind. It was after a protest in a suburban park where twelve health professionals, all masked and socially distanced, sat on the grass holding signs, asking for mandates to be lifted so they could return to work.

VicPol arrived in three coaches. Officers poured out, arresting one woman, ripping her off the ground as she repeated that she had a right to protest.

In the same park, families were picnicking, watching this unfold. Their masked children stopped playing to watch too. I left the park—I had already been arrested twice and wanted the day off.

But later, in a back street as I tried to figure out how to return to my car, I came across another mother with her children.

She looked like she had stepped out of Vogue Living, and the houses around us could have been the magazine’s centerfold: lovingly restored, with manicured gardens.

But the gloss was missing from her eyes.

She talked about what she had just witnessed as though she no longer recognized where she was. The view was the same, but something had fundamentally changed. In her world, the police did not terrorize the public.

And how do you return home when your GPS declares: You can’t get there from here.

The last I saw of the mother in Aldi, she was placing the box her son had been selling her back on the shelf, moving on to another aisle. Her children still sang out their wish lists as the other customers shopped around her in the polite yet awkward silence we used to reserve for libraries and funerals.

Michael Gray Griffith

29/01/25

Crikey that was tough to read, all the best. Busted system.

Wow Michael…..just wow. I was transported along with you and actually “felt” the despair of these people that you so aptly portrayed in your piece….😓🙏